Pushing back against price hikes: Strategies for combating rising drug costs

When the prices of two generic medications skyrocketed, health systems worked to rein in costs while ensuring patients continued to receive high-quality care.

Responding to sticker shock

The wholesale acquisition costs (WACs) of two commonly used cardiovascular medications shot up between 2012 and 2015, following their acquisition by Valeant Pharmaceuticals. During that period, nitroprusside’s WAC increased 30-fold, from $27.46 to $880.88 per 50 milligrams, while iso-proterenol’s WAC grew nearly 70-fold, from $26.20 to $1,790.11 per milligram (N Engl J Med 2017;377[6]:594-5).

Dealing with rising drug costs wasn’t a new experience for pharmacists at the Cleveland Clinic, who are responsible for managing the health system’s medication spending. But these price hikes had greater financial implications than most they’d seen in the past. And they were different for another reason, says Umesh Khot, MD, vice chairman of cardiovascular medicine. Nitroprusside and isoproterenol were generic medications with no patent exclusivity, he says, not newly Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved, branded drugs, so large price increases weren’t expected.

Recruited by the pharmacists in 2013 to develop a plan for decreasing spending on the two drugs without compromising patient care, Khot assembled a group of pharmacists, physicians and administrators who identified medications that could be safely substituted for nitroprusside and isoproterenol.

“This truly was a team effort,” Khot says. “We pulled from pharmacy and …, when it came to, should we use the drug or not, we would often go to those clinicians who take care of those patients because they’re the ones who know what their options are and how we can treat them.”

There were scenarios where they couldn’t find suitable alternatives—such as nitroprusside for heart failure patients in the intensive care unit and isoproterenol for electrophysiology testing—so the pharmacy department continued stocking both medications though in smaller volumes.

As a result of their efforts, the Cleveland Clinic saved more than $8.5 million over a two-year period, Khot reported in NEJM Catalyst (online Nov. 20, 2017). The strategy was an economic success because it was a “sustained reduction,” he says. “We were changing the way in which the drug was used. That’s what led to the pricing decreases that we were seeing in terms of the total cost.”

Now, the health system will focus on studying the impact of the medication substitutions on clinical outcomes, says Khot. The first of several studies they’re planning will focus on how blood pressure control changed when clevidipine was added to the formulary as an alternative to nitroprusside for patients with aortic dissection.

“We haven’t seen any signals of problems,” Khot says.

Multipurpose checklist

Also facing increases in costs for nitroprusside and isoproterenol, the University of Utah employed a checklist strategy that they default to during drug shortages (Pharmacotherapy 2017;37[1]:36-42). Similar to the Cleveland Clinic, the University of Utah team researched alternatives to nitroprusside and isoproterenol and removed the high-cost drugs from the formulary where there were acceptable substitutions. Following their checklist, they also studied purchasing, inventory and dispensing practices for the expensive medications and warned prescribers and administrators about the potential for increased prices to impact budgets.

When consulted by the pharmacists, the physicians pointed out, among other things, that the iso-proterenol kept on cardiac arrest crash carts wasn’t often used. As a result, isoproterenol was removed from the carts and the pharmacy department cut back its order, stocking just enough of the drug to have it available “in a back room if physicians needed it for patients with an extremely low heart rate,” says Erin Fox, PharmD, the system’s director of drug information. “Our clinicians liked having it [on the crash carts] just in case they needed it, but once the price got jacked up, it wasn’t sustainable. … They were very comfortable taking it off the crash carts.” That one change saved about $1 million per year, according to Fox.

Though designed to help them handle drug shortages, the checklist proved to be an effective tool for handling price hikes, she adds. They plan to use it again, if needed, in part because it helped them move fast. With shortages, she explains, “we always have to move rapidly, but with really high-priced drugs, we’ve also been able to move pretty quickly.”

When in 2015 Fox testified at a U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging hearing on sudden price hikes of generic medications, she told senators that the University of Utah would have spent an additional $1.6 million for isoproterenol and $290,000 more for nitroprusside if they hadn’t made changes after Valeant increased prices.

Raising the problem’s profile

Although the nitroprusside and iso-proterenol price hikes are extreme examples, hospitals and health systems are finding they need strategies to manage the rising costs of the medications they administer, including some generic drugs.

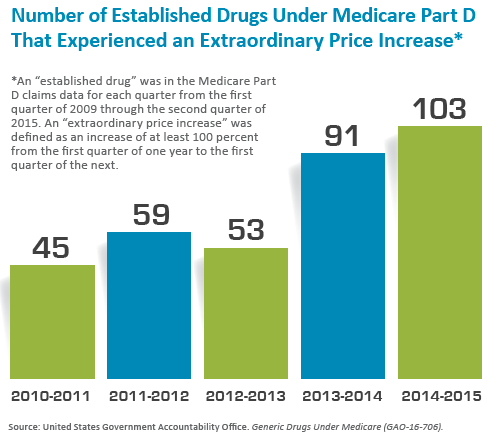

In 2016, the U.S. Government Accountability Office told Congress that the prices of most generic drugs available under Medicare had declined between 2010 and 2015, but about one-fifth of the 1,441 drugs in the “established basket” had “extraordinary price increases” of at least 100 percent (see figure below). Such price hikes have tended to occur when companies buy older generic medications that don’t have the type of competition common immediately after a branded drug loses its patent. A glaring example that drew national attention occurred when Turing Pharmaceuticals increased the price of the AIDS medication daraprim from $13.50 to $750 per tablet.

“That kind of pricing change, particularly in generic drugs, is unprecedented,” Khot says. “In history, typically, generic drugs have been overall cost reducing.”

Fox says she’s encouraged by the federal government’s recent efforts to curtail price hikes. The Federal Trade Commission held a conference in November to explore drug prices and competition, and FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, has vowed to approve more generic medication suppliers if they meet certain standards. Since 2015, the FDA has approved four additional generic versions of nitroprusside and one more of isoproterenol. The price of the medications have dropped 65 percent and 25 percent, respectively, from their peaks, according to Vizient, Inc., which tracks drug prices.

“I’m hopeful that the public shaming is working a little bit,” Fox says. “What I think has worked is all of the media attention helped to focus FDA’s attention on what they can do to help.”

Shaking up the supply side

Meanwhile, some health systems have decided to take matters into their own hands. Intermountain Healthcare, Ascension, SSM Health and Trinity Health announced in January that they will collaborate with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to form a nonprofit company that will manufacture generic medications on its own or use contract manufacturing organizations to make drugs.

“It’s an ambitious plan, but healthcare systems are in the best position to fix the problems in the generic drug market,” Intermountain Healthcare Chief Executive Marc Harrison, MD, said in a press release. “We witness, on a daily basis, how shortages of essential generic medications or egregious cost increases for those same drugs affect our patients. We are confident we can improve the situation for our patients by bringing much needed competition to the generic drug market.”

Fox thinks the concept could work well if the nonprofit generic drug company is able to manufacture the drugs whereas relying on contract manufacturing organizations would be risky. “If they take a contract manufacturer that has poor quality, then we’ll just have a shortage of this nonprofit’s product,” she says. “[I]t’s a really interesting concept, and I wish them all the luck. But I think we’ll have to wait and see what happens.”