Extracorporeal CPR for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: New research fails to provide answers

Extracorporeal CPR and conventional CPR are associated with similar rates of survival and neurologic outcomes among patients with refractory out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, according to new findings published in the New England Journal of Medicine.[1] Does this new analysis help make the case for extracorporeal CPR going forward? Or are there still just as many questions as before?

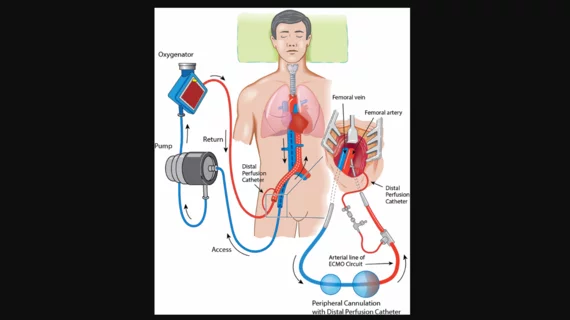

“When there is no return of spontaneous circulation after advanced life-support measures are taken, extracorporeal CPR (the addition of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to standard advanced cardiac life support) can be initiated to restore perfusion with the goal of limiting hypoxic brain injury and allowing for the possible identification and treatment of the underlying cause of the cardiac arrest,” wrote first author Martje M. Suverein, MD, a specialist with the department of intensive care at Maastricht University Medical Center in the Netherlands, and colleagues. “However, evidence with regard to the effect of extracorporeal CPR on survival and neurologic outcomes in observational studies and randomized, controlled trials involving out-of-hospital cardiac arrest remains inconclusive.”

Hoping to shine more light on this topic, Suverein et al. performed the INCEPTION trial, a multicenter study comparing the extracorporeal with conventional CPR. For the team’s analysis, a total of 134 patients presenting with witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest were randomly assigned one of the two treatment options. In all cases, there was no return of spontaneous circulation within 15 minutes.

Overall, the authors found, the percentage of patients who survived with a favorable neurologic outcome was 20% for the extracorporeal CPR group and 16% for the conventional CPR group. The mean time from the start of cardiac arrest to the arrival of emergency personnel was 8 minutes. The mean time from the start of cardiac arrest to arrival at the hospital was 36 minutes for the extracorporeal CPR group and 38 minutes for the conventional CPR group.

Suverein et al. had originally thought they may see a more substantial improvement among patients in the extracorporeal CPR group. This early hypothesis was, at least in part, due to the results of the ARREST trial, a small, single-center study focused on the same topic.

However, the group noted, there are key differences between the INCEPTION and ARREST trials. The ARREST trial, for instance, focused on fewer patients at only one location. Also, it appeared to take longer to commence extracorporeal CPR for clinicians in the INCEPTION trial, a difference that may be due to less experience.

“The potential of extracorporeal CPR in an appropriate setting may seem evident,” the authors concluded. “However, our findings suggest that the reproduction of such superior results is not self-evident when extracorporeal CPR is pragmatically implemented, even in cardiosurgical centers where providers are experienced in its use. Centers that provide extracorporeal CPR or are in the process of implementing the approach should critically assess their logistics and subsequently evaluate the efficacy of the procedure. Future research should address indications and outcome predictors.”

Read the full analysis here.

Another perspective: ‘The future of extracorporeal CPR remains in question’

A separate editorial, also published in the New England Journal of Medicine, examined what these findings might tell us about the potential of extracorporeal CPR.[2] The editorial was written by co-authors John F. Keaney, Jr., MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and Thomas Münzel, MD, of the University Medical Center Mainz in Germany.

Keaney and Münzel wrote that these findings were “likely to be disappointing to proponents of extracorporeal CPR.” However, they added, this doesn’t mean there is suddenly no hope for the future of this therapy; it just means additional research is still required before extracorporeal can realistically be recommended for patients presenting with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

“Available data do not yet support the broad use of extracorporeal CPR in patients with witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” Keaney and Münzel concluded. “Definitive evaluation of extracorporeal CPR will probably require studies on a much larger scale with robust statistical power to estimate any potential benefit of this resource-intensive strategy. Until then, the future of extracorporeal CPR remains in question.”

Read the editorial here.